Teem

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Anthony Reynolds Gallery, London

— Log in to watch the artist video if you have been given an access

- Title

- Teem

- Gallery

- Anthony Reynolds Gallery, London

- Year

- 2007

- Duration

- 27 min 31 s

- Format & Technical

Three screen installation, various lenghts, looped, colour video shot on mobile phone transferred to file, no sound

10 + 1 AP

- Produced by

- Postproduction

- Photography

- Cast

- Commissioned by and first presented

“This small town can bore you to death. At least, there are the sleeping soldiers to make things more exciting”, says Jenjira, the protagonist of Cemetery of Splendor, 2015, the last film written and directed by Apichatpong Weerasethakul. That may accentuate the political aspect of sleeping as a form of resistance, associated with biopolitics, “expressed as a control that extends throughout the depths of the consciousnesses and bodies of the population”[1].

During the 19th century, the bond between a sleeping and an awakening state started being assembled in a way that asleep was understood as retrogression to a more primitive condition. However, sleep nowadays is “political through and through”[2]. That is the cases of the three-channel video installation Teem. In it, the filmmaker shows Teem (Chaisiri Jiwarangsan), his partner, trying to sleep, on three mornings in a row. Apichatpong, while disrupting his partner’s mission to hibernate, shows that this is one of the rare moments when we abdicate our bodies to the care of others while conserving ourselves.

Most of the time the divine or supernatural is presented through the ordinary on Weerasethakul’s work. For example, on Cemetery of Splendor through the appearance of the goddesses from Laos, before Jenjira, with the shape of a regular human being. The wonder is presented through their story: “The spirits of the dead kings are using these men’s spirits for their battles”. It seems like Apichatpong is trying to tell us that we need to look closer to reality, to Teem sleeping carefully, since it can unveil amazing potentialities. In a similar tone, Ben Abel says: “When they sleep, people’s spirits leave the body, and bring back messages, sometimes in dreams”[3].

For his multi-part project Primitive, 2009, which deals with the history of Nabua, there is also a reference to a sleepy village, but in this case as a place full of repressed memories. Here, as well as in Teem, sleep is a metaphor on which power performs as a sort of meditative state that can’t be controlled or instrumentalized.

Tiago de Abreu Pinto

[1] Hardt, M. & Negri, A., Empire. Cambridge. Harvard University Press, 2000.

[2] [2] Williams, Simon J., The Politics of Sleep: Governing (Un)consciousness in the Late Modern Age, New York. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

[3] [3] Anderson, Benedict, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Viena. SYNEMA, 2009.

Stills

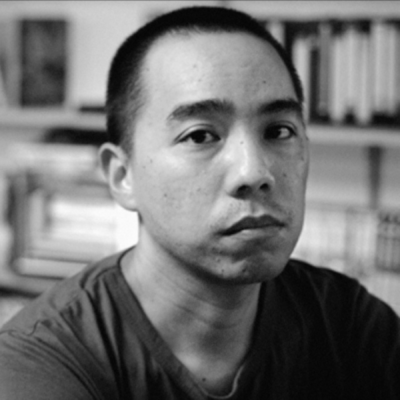

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

- Artist

1970, Bangkok

Apichatpong Weerasethakul is an independent film director, screenwriter, and film producer –he founded Kick the Machine in 1999–, who presents his productions both in cinema circuits and contemporary art scene. The main themes he reflects include dreams, nature, sexuality, and Western perceptions of Thailand and Asia. All of them are displayed in unconventional narrative structures, light and time. Feature films include Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, winner of the 2010 Cannes Film Festival; Tropical Malady, Jury Prize at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival; Blissfully Yours, top prize in the Un Certain Regard program at Cannes 2002; Syndromes and a Century, which premiered at the 63rd Venice Film Festival and was the first Thai film to be entered in this competition; or Cemetery of Splendour, which premiered in the Un Certain Regard section at Cannes 2015. Among his installations in art centers stand out the shows at Tate Modern, London, 2016; SCAI Bathouse, Tokyo, 2014; Hangar Bicocca, Milan, 2013; UC Berkeley Art Museum, Berkeley, 2013; or The New Museum, New York, 2011. He has also participated in the 11th Sharjah Biennial; Documenta 13; VideoZone 4; or the 7th International Istanbul Biennial, to name but a few.