Arnau Horta i Sellarès

- Curator, Participant

1977

Arnau Horta is an independent curator, art critic and researcher. In Spain, he curated projects for the MACBA, the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, the CCCB, Sónar, Caixafòrum, the Filmoteca de Catalunya, the philosophy festival Barcelona Pensa and La Casa Encendida, among others. He is Professor at the European Institute for Design (IED), and a usual contributor to the supplements ‘Cultura/s’ (La Vanguardia) and ‘Babelia’ (El País).

22 March 2017

Related Activities

‘The Audiovisual Unconscious I’. Martin Arnold

26 May — 10 June 2016

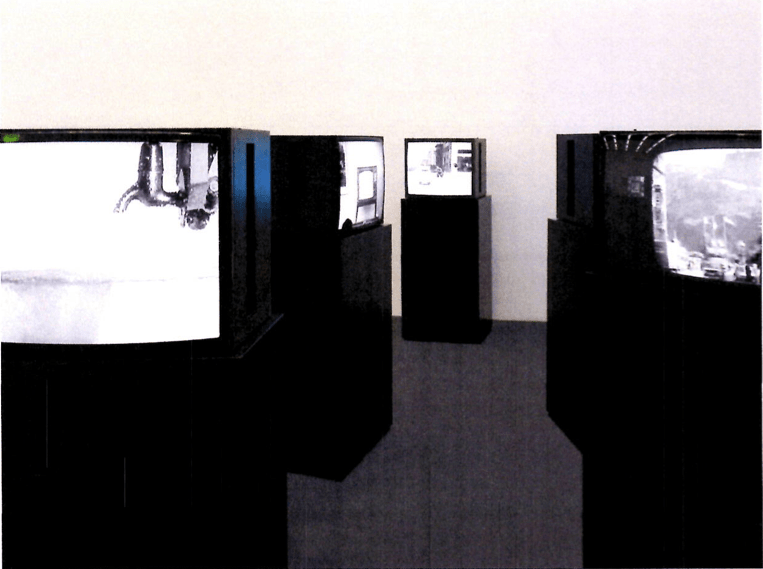

— 'Members Only', an audiovisual installation by Martin Arnold

- Artists

- Martin Arnold

- Curators

- Arnau Horta i Sellarès

- Venue

- CCCB. Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona

- Contributor

- Foro Cultural de Austria de Madrid and CCCB Xcèntric

- Price

- Free admission

- Date and hours

- 26 May — 10 June 2016 Add to calendar

Add to calendar

Using a similar principle to that of his films, in the installation, ‘Members Only’, Arnold proposes an experimental review of the gag. In this case, however, the audiovisual material is provided not by black and white Hollywood films but by cartoons. Thanks to his manipulation, the innocence of the images is replaced by a succession of histrionic and violent actions. The characters are fragmented and mutilated, set against a completely black background. Hands that twist, tongues that move, mouths that articulate meaningless words… Here, the harmless original scenes are transformed into creepy or disturbing phantasmagorias, full of frustration and aggressiveness, which, in some cases, also contain a disconcerting erotic urge.

‘The Audiovisual Unconscious II’. Martin Arnold & Peter Tscherkassky

Tuesday 7 June 2016, 8 pm

— Screening and presentation at the presence of the filmmakers

- Artists

- Martin Arnold and Peter Tscherkassky

- Curators

- Arnau Horta i Sellarès

- Venue

- CCCB. Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona

- Contributor

- Foro Cultural de Austria and CCCB

- Price

- Free admission

- Date and hours

- Tuesday 7 June 2016, 8 pm Add to calendar

Add to calendar

Martin Arnold and Peter Tscherkassky are two of the foremost representatives of Austrian experimental cinema. Despite the differences between their working methodologies and the way they use found footage, both Arnold and Tscherkassky seem to want to reveal a whole series of meanings hidden within the audiovisual continuum; things which, somehow, were already there, but which can only be extracted and displayed by means of a process of alteration, aggression and alienation of cinematographic narratives and techniques. This layer of concealed meaning that seems to emerge from the depths of dreams and original images is what we call the ‘audiovisual unconscious’.

Programme

– Passage à l’acte, Martin Arnold, 1993

– Alone. Life Wastes Andy Hardy, Martin Arnold, 1998

– Outer Space, Peter Tscherkassky, 1999

– Instructions for a Light & Sound Machine, Peter Tscherkassky, 2005

DCP screening. Presentation by the filmmakers followed by a debate with the public.

‘The Audiovisual Unconscious III’. Peter Tscherkassky & Eve Heller

Wednesday 8 June 2016, 6:30 pm

— Masterclass with the artists

- Artists

- Peter Tscherkassky and Eve Heller

- Curators

- Arnau Horta i Sellarès

- Venue

- CCCB. Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona

- Contributor

- Foro Cultural de Austria and CCCB

- Price

- Free admission

- Date and hours

- Wednesday 8 June 2016, 6:30 pm Add to calendar

Add to calendar

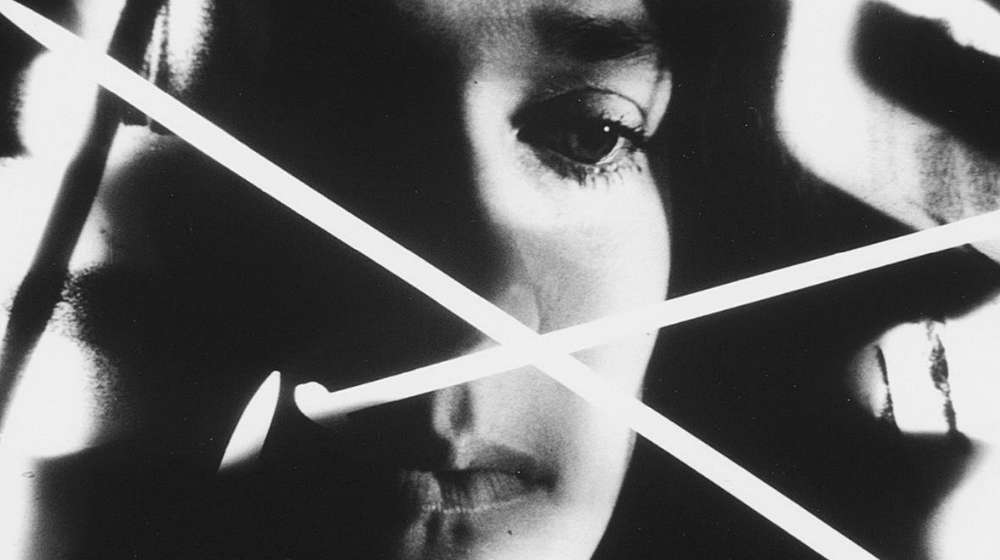

You might say that while Arnold brings an experimental approach to the comic gag, Peter Tscherkassky (Vienna, 1958) does the same thing with sequences of suspense, horror and violence. In Outer Space (1999), for example, Tscherkassky manipulates scenes from the horror film The Entity (1982) to heighten the uneasy atmosphere of this story about a paranormal being that sexually abuses the protagonist. Tscherkassky’s methodology consists in a direct intervention in the mechanics of the cinema. Here, it is not so much the sounds and images as the filmic supports themselves (the film and the soundtrack) that are subjected to a traumatic alteration which radically modifies their continuity. Technical subversion allows new meanings to break free from inside the original images and sounds.

In this masterclass, Tscherkassky and Eve Heller (1961) bring together their respective creations and their ways of seeing the audiovisual unconscious.

‘The Audiovisual Unconscious IV’. Martin Arnold

Thursday 9 June 2016, 6:30 pm

— Masterclass with the artist

- Artists

- Martin Arnold

- Curators

- Arnau Horta i Sellarès

- Venue

- CCCB. Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona

- Contributor

- Foro Cultural de Austria and CCCB

- Price

- Free admission

- Date and hours

- Thursday 9 June 2016, 6:30 pm Add to calendar

Add to calendar

Martin Arnold (Vienna, 1959) deconstructs scenes from classic Hollywood films into small fragments that he slows down and repeats frenetically. The result is a series of loops that disrupt the continuity of the original material and strip it of its narrative meaning. As a result of this radical process of alienation and denaturalization of the relation between sound and image, the scene becomes a Dadaistic gag in which the characters’ actions acquire surprising new meanings. In this way, the family breakfast scene that Arnold deconstructs in ‘Passage à l’acte’ (1993) becomes a violent exchange of blows and monosyllables between the film’s characters. Similarly, in Alone. ‘Life Wastes Andy Hardy’ (1998), the sequence of a son kissing his mother suddenly seems like something quite different, conveying a quite distinct type of affection to that of a mother-son relationship.

David Hall. ‘TV Interruptions (7 TV Pieces)’

18 — 23 May 2017

- Artists

- David Hall

- Curators

- Arnau Horta i Sellarès

- Venue

- Museu Picasso de Barcelona

- Date and hours

- 18 — 23 May 2017 Add to calendar

Add to calendar

‘TV Interruptions (7 TV Pieces) were my first works for TV, and are a selection from the original ten. Conceived and made specifically for broadcast, they were transmitted by Scottish TV during the Edinburgh Festival in 1971. The idea of inserting them as interruptions to regular programs was crucial and a major influence on their content. That they appeared unannounced, with no titles (two or three times a day for ten days), was essential. These transmissions were a surprise, a mystery. The TV was permanently on but the occupants were oblivious to it, reading newspapers or dozing. When the TV began to fill with water, newspapers dropped, the dozing stopped. When the piece finished, normal activity was resumed. When announcing to shop assistants and engineers in a local TV shop that another was about to appear, they welcomed me in. When it finished, I was obliged to leave quickly by the back door. I took these as positive reactions.’ — David Hall, 1990

A-PLACE: Creating space through sound

Tuesday 21 November 2023, 3 — 4 pm

- Participants

- Carolina Jiménez, Arnau Horta i Sellarès, ALMARE Collective, Ananú Gonzales Posada and Aura Satz

- Moderator

- Victoria Sacco

- Venues

- Almanac Barcelona

- Date and hours

- Tuesday 21 November 2023, 3 — 4 pm Add to calendar