Fito Conesa

- Artist

1980

Fito Conesa studied Fine Arts at the University of Barcelona, the city where he lives and works. With a multifaceted work that encompasses installation, video and sound exploration, some of his works are conceived as an exhibition of the artist himself and his geographical context of origin; others incorporate different elements of cultural history and the contemporary world; and others dissect the everyday.

Since 2008, he has exhibited in spaces such as the Aparador del Museu Abelló in Mollet del Vallès (2008), CaixaForum in Tarragona (2009), Centro Cultural Español in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (2014), La Naval in Cartagena (2015) and Espai 13 at the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona (2018). His work can be found in collections such as the Fundació Banc Sabadell, the University of Granada, the City Council of Valls and MACBA in Barcelona.

Related artist videos

- Title

- Anoxia. A Constant Prelude

- Year

- 2023

- Title

- El Reparo

- Gallery

- House of Chappaz & JOEY RAMONE

- Year

- 2021

- Duration

- 5 min

- Format & Technical

Video HD

- Courtesy

- Fotos

Related galleries

House of Chappaz

- Address

- Calle Caballeros 35/Carrer de Ca l'Alegre de Dalt 55, 46001, Valencia/08024, Spain/Barcelona

House of Chappaz is born from the evolution and transformation that Espai Tactel gallery has had both at work and personal level since its founding in 2011, maintaining its essence but expanding its field of action. This transformation has occurred in a natural way and its objective is that the gallery founded in València by Ismaël Chappaz, and to which in 2018 Oriol Armengou and Ferran Mitjans (Toormix) were added, continues to grow, expand and create new alliances to continue spreading its lines of action and its ideas in pursuit of the most current contemporary art.

Following the lines marked by the previous project, and focusing on topics such as the future, gender theories, contemporary aesthetics and many others, House of Chappaz is a project that evolves over time through risk and commitment to young (and not so young) very promising talents.

Related Activities

Fito Conesa. ‘Anoxia. A Constant Prelude’

15 November — 10 December 2023

- Artists

- Fito Conesa

- Venues

- Centre d’Art Tecla Sala

- A project by

- Project awarded at the 9th Edition of the Video Creation Award. A co-production between the Territorial Centers of the Public System of Visual Arts Equipment of Catalonia, Santa Mònica, Department of Culture of the Generalitat of Catalonia* and LOOP Barcelona.

*Centres Territorials del Sistema Públic d'Equipaments d'Arts Visuals de Catalunya:

ACVic Centre d’Arts Contemporànies, Vic; Bòlit, Centre d'Art Contemporani. Girona; Fabra i Coats: Centre d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona; M|A|C Mataró Art Contemporani; Mèdol - Centre d’Arts Contemporànies de Tarragona; Centre d'Art la Panera, Lleida; Lo Pati - Centre d'Art Terres de l'Ebre, Amposta i Centre d'Art Tecla Sala, L'Hospitalet de Llobregat.

- Date and hours

- 15 November — 10 December 2023 Add to calendar

- Additional info

- Opening 14/11/2023, 19h.

From Tuesday to Saturday: from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. and from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m. Sundays and public holidays: from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. Monday weekdays: closed.

Add to calendar

Cruisers traverse the Mediterranean from Barcelona, spinning a web of unpredictable constellations, like someone who spends their free time connecting dots on a piece of paper so frequently that it begins to tear.

Late capitalist denialism is, in reality, the natural outcome of our fear of not knowing how to manage collapse, change, and bad news. We are incapable of grasping action and movement beyond the guilt that paralyses us.

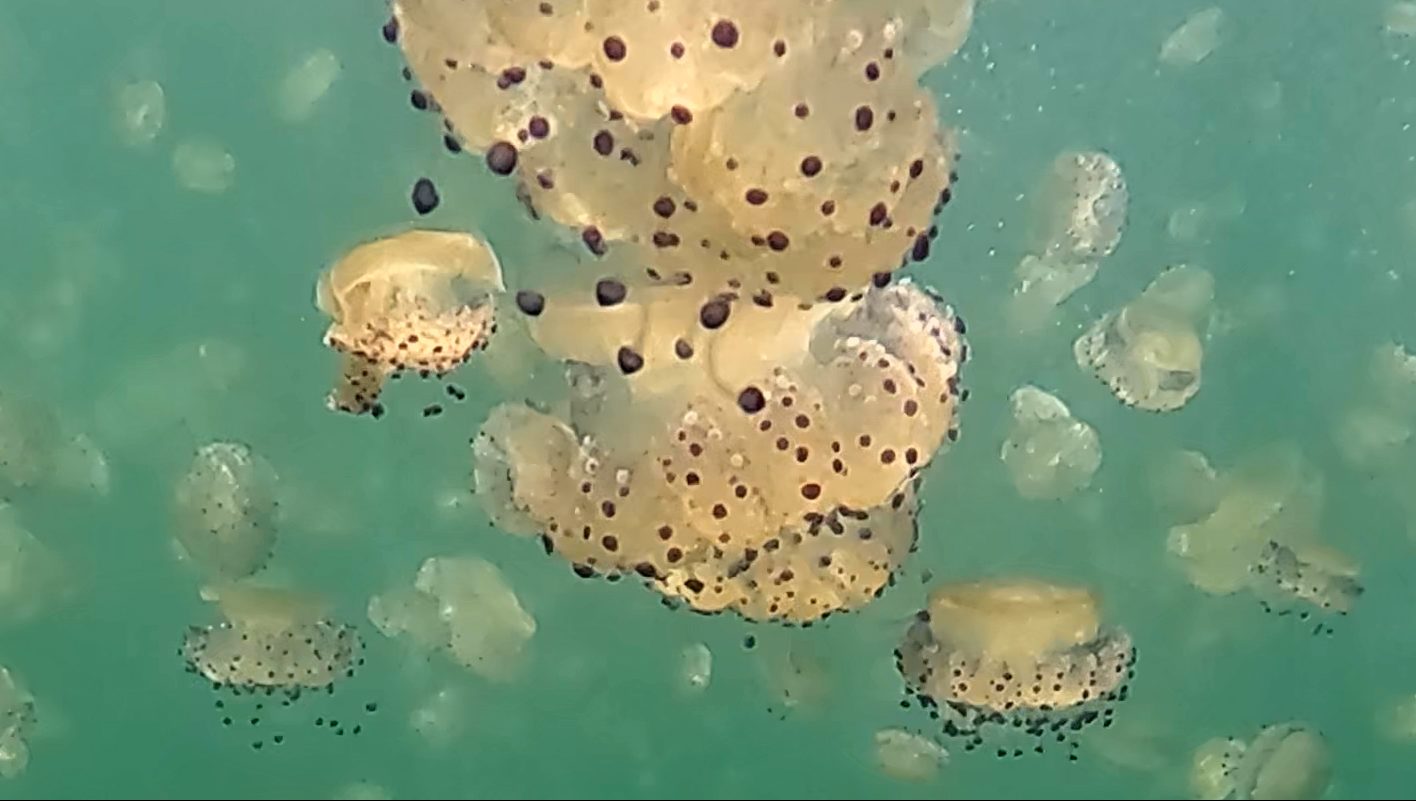

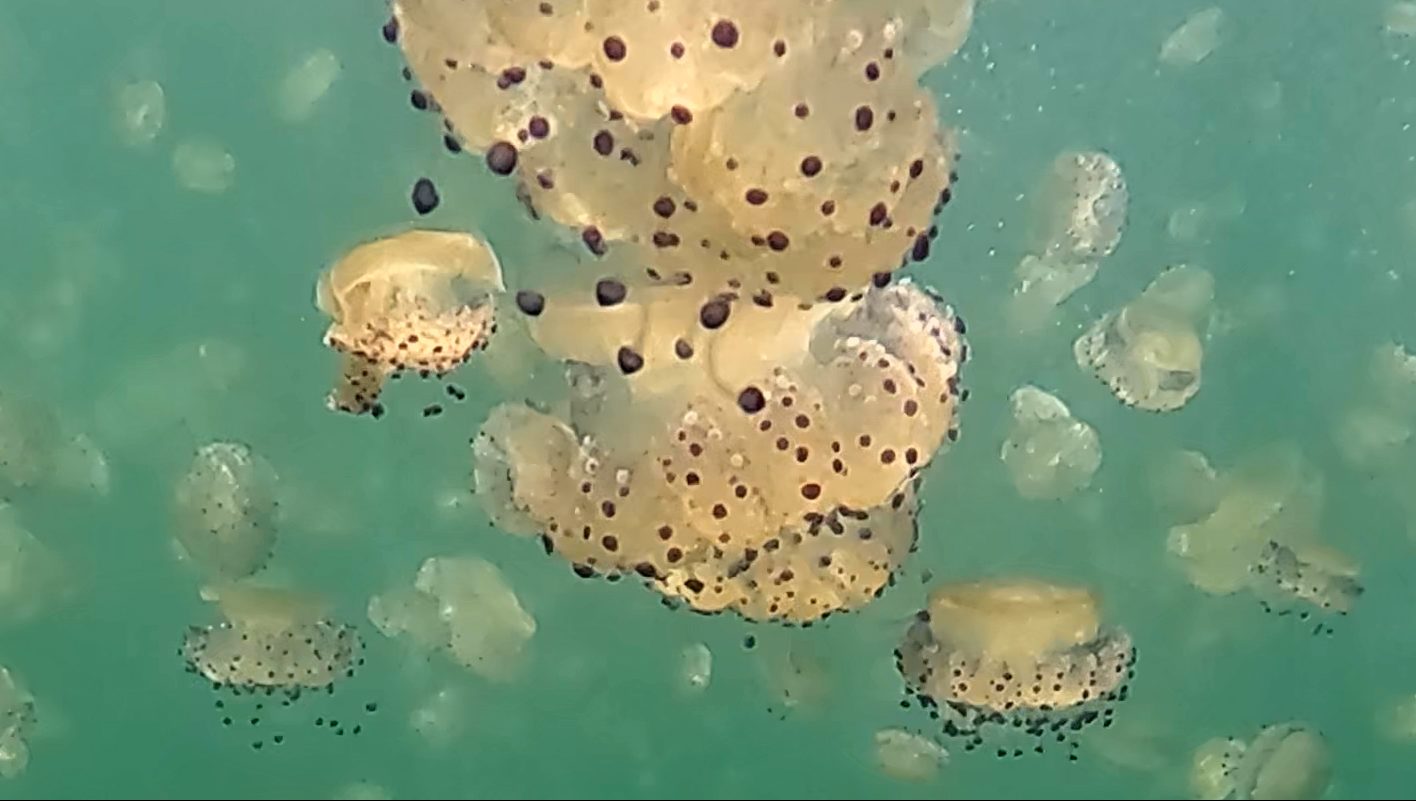

Anoxia. A Constant Prelude is an opera that gradually narrates some of the most evident issues that the Mediterranean Sea has been subjected to; a visual song that expands upon our questionable coexistence and recounts in thermal glissandos the darkness that unfolds, yet it does not rely solely on fatalism as the only possible melody.

It is an audiovisual work created in several phases, with diverse voices, multiple sensitivities, and real alliances; a naumachia in three acts.

The exhibition in Centre d’Art Tecla Sala is split into two parts: a foreword that serves as an overture to the main piece which the project is named after, followed by the projection of the debut opera on a large screen positioned at the back of the room. In the foreword or prologue space, all the process and preparation materials can be seen and consulted, both from the compositional and conceptual aspects.

The material comes from various municipal and museum archives and, along with the scores and other elements/objects (plans, texts, small sculptures, newspaper archives that have appeared throughout the research), will place the viewer in a specific conceptual, emotional, and political framework.

Anoxia, an opera in three acts that offers various approaches to the contemporary issues of the Mediterranean Sea.

*Anoxia is the lack (or almost lack) of breathable oxygen in cells, tissues of an organism or in an aquatic system.

Cecilia Bengolea, Fito Conesa, Carles Congost, Marco Godoy, Adrian Melis and Teresa Serrano.’Claiming the Echo’

6 July — 25 September 2022

— Film Programme, Centro Cutural España en México

- Artists

- Cecilia Bengolea, Fito Conesa, Carles Congost, Marco Godoy, Adrian Melis and Teresa Serrano

- Venue

- Centro Cultural de España en México(CCEMx)

- Date and hours

- 6 July — 25 September 2022 Add to calendar

Add to calendar

Over the centuries, there has been much debate about the meaning of music and composition as linguistic forms. Although it would be difficult to affirm the universality of musical language without falling into hasty generalizations, it can be said that music functions as a communication tool, with its own specific codes of expression and representation, intonation and vocabulary.

As it happens with linguistic variety to distinguish among people who speak the same language (‘dialects’), in the musical field it is also possible to differentiate between different genres or styles. According to the academic classification, the factors to be taken into account in this case would be the ‘instrumentation’, the ‘design’ and the ‘intention’ of a composition, as well as its ‘cultural peculiarities’ and the ‘historical and geographical setting’ of its production.

According to this, you would have genres that use classical or acoustic musical instruments, and others that are produced virtually, with electronic nuances and synthesizers; there are genres that are a mixture of different music, and others that claim their purism. Some follow an exact score and others are based on improvisation. There are compositions designed to accompany singing or dancing, as well as to cause moments of recollection and reflection. There is traditional or popular music, as well as evangelical or religious music. There are rhythms resulting from youth movements in opposition to the system, as well as repeated litanies addressed to a saint or melodies related to the protests of the working class.

As this video selection wants to show, we could say that music is a hybrid, diverse, plural, heterogeneous phenomenon, but present in everyday life or in the memory of each one. That is a communication tool with a strong political, social, liturgical, visionary or entertainment character.

Thus, in Helicon (2018) by Fito Conesa (Cartagena, 1980), we hear a mystical song addressed to the Earth before the Apocalypse; and in Reclamar el eco [Reclaiming The Echo] (2012) by Marco Godoy (Madrid, 1986) the slogans pronounced in the protest demonstrations in Spain. The video Amapola (2017) by Teresa Serrano (Mexico City, 1936) proposes a sad melody that celebrates the symbolic resistance of the poppy flower to the drug trafficking network in Mexico, while Glorias de un futuro olvidado [Glories of a forgotten future] (2016) by Adrián Melis (La Habana, 1985) presents a group of women who remember their past in the time of Capitalist Cuba through some songs. On the other hand, Wonders (2016) by Carles Congost (Olot, Girona, 1970) uses resources close to musical biopic and performance to reflect on the social and personal repercussions of success and failure; and Dancehall Weather (2017) by Cecilia Bengolea (Buenos Aires, 1979) proposes a mix of various choreographic videos filmed between 2014 and today, where dancehall music constitutes an important moment of affirmation and aggregation.

We could reaffirm, then, that the meaning (or interpretation) attributed to music has to do, essentially, with the cultural horizon from which it is produced or heard, but that its existence is verified from one side of the planet to the other. As a resonance, a repercussion, or a continuous reflection. An infinite echo beyond time and space.

OPENING: Fito Conesa and Siddarth Gautam Singh. ‘Ménagerie’

Tuesday 8 November 2022, 7 pm

- Artists

- Fito Conesa and Siddharth Gautam Singh

- Venue

- Born Centre de Cultura i Memòria

- Date and hours

- Tuesday 8 November 2022, 7 pm Add to calendar

Add to calendar

Ménagerie is a French word that could be translated as a ‘wild animal house’, a ‘wild animal exhibition’ or a ‘wild animal refuge’ and which designates a historical establishment intended to host and display captive wild animals under the custody of humans. Generally speaking, the animals exhibited there were mostly exotic by the standards of the country where the menagerie was located.

Fito Conesa and Siddarth Gautam Singh would like to break this anthropocentric notion of cataloguing, cramming and wanting to impose an inquisitorial order upon nature, like those who trap a moment in a photograph, renouncing the invisible synaesthesia.

In the mid-20th century, French composer Olivier Messaien already (probably unknowingly) suggested other ways of approaching this notion of classifying nature and freezing time. In his Catalogue of birds he toyed with a new possibility of embracing nature, a poetic attempt to establish some kind of sound register to the melodies and songs of birds translated into musical language, much like when you hum a song and then clumsily attempt to play the melody on a piano.

This modern-day Menagerie presents itself as the exquisite corpse of beings that indistinctly inhabit the past and the present, and which will surely be the ones who draw the future. Let us imagine for one moment (in an exercise in radical concentration) that there are also new possibilities hidden within the permafrost or fossil ice, and that the ice that rapidly becomes water not only contains ancient bacteria and beings, but perhaps also (and in a context of extreme positivism) those species frozen in the past will be those that will reorganise the future.

We are offered a recital of ancient sounds, iridescences and a new ecosystem that will become formalised in a display which, in the space of an hour, will show us new chapters of these non-human beings and narratives.