La Casa Elizalde

- Address

- Carrer València, 302, 08009, Barcelona

- Phone

- 934 88 05 90

- Website

- www.casaelizalde.com

- Map

- View map

Ariadne Was Never Our Goddess proposes unravelling the dominant social and political structures of our societies to reweave new threads of connection that enable us to dismantle othering and establish a space of horizontal relationships. With a clear questioning spirit, the project challenges the Western historical projections of femininity, not only in visual art and literature but also in social and political constructs, as well as in matters of race and class.

Through a reinterpretation of the work of artist Maria Alcaide, The Managed Hand, Ariadne fades and blends into American nail salons, spaces where those who care for others seek to be cared for themselves. The result is a repetition of power relations in which subordinated bodies simulate the display of dominant privilege. In these spaces, conversations, longings, and dreams blur amid the sounds of nail files and the soft purple light of lamps, where power categories invert, yet violence resurfaces.

Maria Alcaide’s work borrows its title from sociologist Miliann Kang’s 2008 book The Managed Hand, an anthropological study on the social and economic conditions of America’s highly precarious youth. Drawing from her own experience, in which Alcaide worked in public-facing roles, offering her physical labour in service to others and thus placed on a lower scale of rights, she began an in-depth investigation into the performativity of work associated with bodily services. Her work exposes the systemic violence exerted on female, racialized, and lower-to-middle-class subjects. Alcaide delves into this ecosystem of service performativity through the specific context of nail salons, where these power dynamics play out among the same oppressed bodies, simulating the privilege of class. In an allegory that inverts the myth of Ariadne, it is not Theseus who must find his way out of the labyrinth but rather those who place their bodies at the service of those who can afford it.

The conversation will revolve around the representation of the queer migrating experience through documentary film, what are the potentials and limitations of (re)presenting this type of story through the cinema, and what is the filmmaker’s space in relation to the protagonists.

Documentary cinema is no stranger to the current revolution in science and technology. Nor is it impervious to critical reflections that warn of the potential dangers associated with these advancements. From three different perspectives, the participants in this conversation will address these challenges.

This documentary provides insight into the experience of immigrating through the lens of two queer refugees, who are each in different stages of this process in Brussels. Through a collective creation method, the immigrants get to choose how to tell their story. This documentary delves into each step of the immigration process, as well as how the queer immigrants carve out their space in the urban landscape they find themselves in. By narrating, sharing, and shedding light on their origins, they can make themselves, their identities, and their stories visible, allowing them to establish their own sense of belonging derived from a unique set of experiences.

On December 13th at 19h the talk Documentary Film, Migration and Queer Subjectivity will take place at La Casa Elizalde with Camila Flores-Fernández and Victoria Sacco.

Project co-financed with funds from Creative Europe and A-PLACE Linking Places Through Networked Artistic Practices programme.

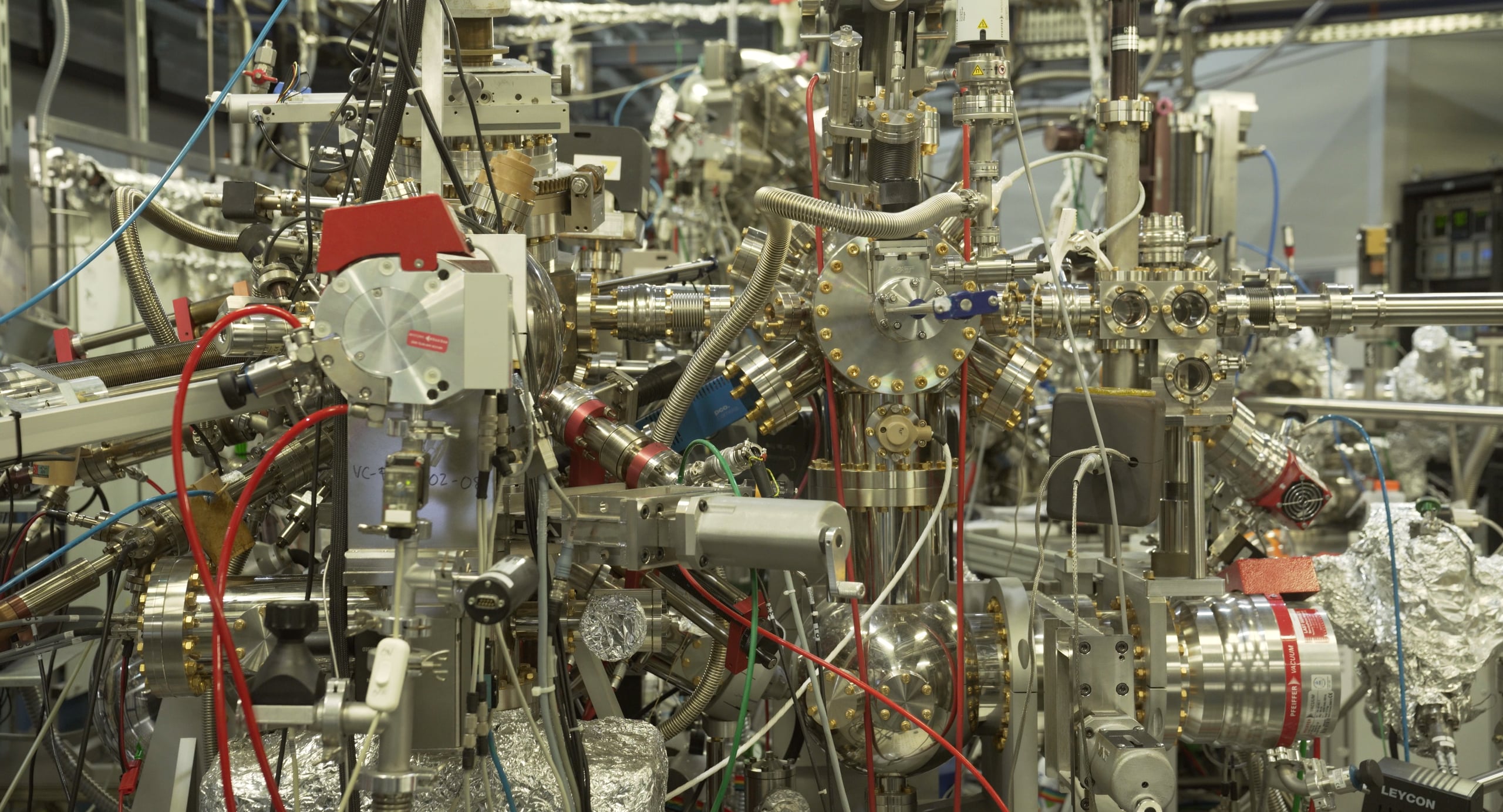

Whilst the machine grows and grabs all the headlines, the forest watches and heeds a silent warning. This documentary project is framed as a dialogue between nature and technology. It was filmed at two locations: the interior and exterior of the ALBA Synchrotron, an impressive building located on the outskirts of Barcelona, considered the most complex machine in the southwest of Europe. As the focus shifts between each location, the philosopher Juan Arnau provides his reflections, he is also an astrophysicist, specialist in Eastern cultures, and staunch defender of humanism in the age of technological distractions.

On November 29th at 19h the talk Ciència, tecnologia i mirada documental will take place at La Casa Elizalde with Pau Faus, Pau Subirós and Victoria Sacco.

Project co-financed with funds from Creative Europe and A-PLACE Linking Places Through Networked Artistic Practices programme.

This exhibition builds on intermingling ideas of uncertainty and hope; concepts that have been present in Cuban society for decades and that have become increasingly irrefutable on a global scale. With this paradigm in mind, the addressed situations become comparable to the current planetary order imposed by the coronavirus pandemic. The videos by Adrián Melis and Javier Castro put on display a humanity that operates in the latent state of anesthesia–alive but willingly unconscious. The videos transport the viewer to a kind of limbo that suspends all ability to take action, leaving us waiting for an imagined future that will never come. Through their images, the artists speak of what is and what could have been; of latent desire, of potentiality, and of resistance. But they also speak of impotence, of disappointment and of resignation; of possible and impossible futures, of nostalgic pasts and of broken promises. Ultimately, they both speak of the multiple forms of survival that exist in the face of adversity.

Versus. Addressing similar themes, the artists’ discursive strategies are oppositional but oddly complimentary. Melis develops his videos through elaborate planning: with much precision, he positions the camera, gives instructions, and prepares the staging. On the other hand, Castro presents raw material from simple and direct interviews, based on immediacy and spontaneity. To achieve their respective purposes, Melis approaches the privacy of homes as locations, attempting to encourage introspection. Meanwhile, Castro walks through streets and public spaces with direct questioning, looking for answers without filters. Melis collects the memories of past generations, Castro finds his impulse in childhood and youth. However, from an anthropological point of view, both artists complete the same image: one of a complex and bipolar humanity, sustained by hope and disappointment. A humanity built on resignation; on a visceral nostalgia for past glories, and eager for an uncertain future. They coincide in emotion: both artists take a raw, ruthless and ironic look at the intimacy of real lives, revealing the pain of resignation and the anger of nonconformity. They too do not fear eternity.

WORK

What do you want to be? What would you have been?

In The Golden Age (Castro), children take their imaginations to flight and envision their futures; in Glories of a Forgotten Future (Melis) elder women go back in time to the moment when they had once imagined a sweeter future. Nostalgic pasts confront the anticipation of uncertain futures and the longing for something that didn’t occur. Futures that will never be and futures that never were. Jammed between children and elders, young adults struggle in limbo. (the anesthesia of time)

Silence: resignation and defiance

From a fighting stance, The New Man and my father (Melis) and I’m not afraid of eternity (Castro) create dialogue through two complementary combat strategies: insertion and challenge. Melis creates a portrait of his father in the intimacy of his home, taking the blows of Cuba’s political destiny. On the other hand, Castro takes the attacking position, exhibiting the streets and defiant young people who inhabit them. We are facing two diametrically opposed generational attitudes: a resigned Castro generation and a rebellious and challenging youth. Both videos are silent, without argumentation, and display the explicit evidence of an inevitable body language. The real paradox is in the background, since these videos are two different ways of showing the paralysis in face of an uncertain future, disappointment and acceptance. (Silence anesthesia)

The scorpion’s strategy

Here, everyone takes care of me (Melis) and Your silence has a price (Castro) are two pieces through which the artists explore the limits of ethical values, often being displaced by fatigue, helplessness and hopelessness. Melis deceives traitors by revealing the reciprocal game between a supervisor who consents to the illicit activities of his employees so that they can preserve a position without management; Castro confronts people by asking them to calculate the price of their silence. When the future is at a permanent halt, we begin to consciously walk on the edge of the precipice…the only way left is the strategy of the scorpion: ethical suicide. (Ethical anesthesia)